- Home

- Meili Cady

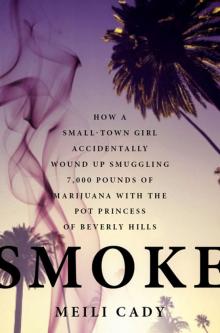

Smoke

Smoke Read online

DEDICATION

FOR MOM AND DAD

AND FOR FIELD

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

PART ONE

GATEWAY

1 ONE TOKE OVER THE LINE

2 FRESH OFF THE BUS

3 THE HEIRESS

4 “AND THE EMMY GOES TO . . .”

5 DOWN AND OUT IN ENCINO HILLS

6 TEAM LL

PART TWO

A BAD HIGH

7 MY DOUGH, MY SHOW

8 LOVE IN THE TIME OF FELONIES

9 HIGH TIMES

10 #008

11 I AM STEPHANIE

12 THE CRIMINALS

PART THREE

CRASHING

13 LOST IN COLUMBUS

14 NO REST FOR THE WICKED

15 WRITTEN ON THE WALL

16 THE OTHER SIDE

17 A DRAMATIC EXIT

18 TARGET OF INVESTIGATION

19 QUEEN FOR A DAY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PART ONE

GATEWAY

1

ONE TOKE OVER THE LINE

The last time I went to a federal building in Ohio, I was escorted in handcuffs by an army of DEA agents carrying submachine guns and enough evidence to send me to prison for forty years. Now I’m escorted by my attorney to meet with the prosecutor to explain how the hell I ended up on a private jet with a quarter ton of weed packed into thirteen suitcases.

The conference room is stale and windowless, much like the interrogation room I was in for four hours while officers grilled me about my friendship with Lisette Lee, the alleged heiress to the Samsung electronics fortune. She was my best friend for four years in Los Angeles, the first close friend I made in town. We were ride or die “partners in crime.” We brought new meaning to the phrase. Growing up, I had a tight-knit group of best friends in Washington, and we shared a lot of friendship bracelets, but none like I shared with Lisette. We both took that ride in the DEA’s SUV, where we sat side by side in matching handcuffs.

I take a seat next to Mike Proctor, my attorney, on one side of a long conference table. Two DEA agents and a prosecutor sit across from us. I’m wearing the same black blazer and figure-hugging pencil skirt I wore when we were arrested, but today the ensemble hangs on me. Staring down a decades-long prison sentence can do a lot to curb a girl’s appetite. I set aside my black quilted Chanel tote, a gift from Lisette in better times, and remind myself to breathe. Mike gives me a reassuring nod. We’ve spent the past four weeks preparing for this moment.

The prosecutor, Tim Pritchard, reminds me of a male mannequin with an athletic build and a poker face. This is the first time I’ve met him, but I met Agent Heufelder, a stern no-nonsense DEA agent, when he put handcuffs behind my back before a trip to DEA headquarters last month. The second agent is here as a formality. I met him on the other end of a submachine gun at our last arrival at the private airport in Columbus.

Tim Pritchard and the DEA agents have pens and pads of paper in front of them, ready to take notes during the interview, and a stack of police documents for reference. Tim explains the terms of the proffer session and asks me if I understand and agree to speak under these terms. After I agree, I feel the energy on the other side of the conference table shift. Tim and Agent Heufelder seem wound up and ready to begin firing questions at me. Mike and I both know that the first thing they will ask, and the thing they will continue to ask until they get a straight answer, is whether I knew it was weed in the suitcases. No one will believe that I didn’t know. Mike is a brilliant attorney and a good man, and he’s helped me prepare for how to handle this moment.

As Tim opens a manila folder in front of him, I take a dry swallow of air. I know what I have to do. “If it’s okay, I’d like to say something before we begin,” I say. Tim looks up from his folder, then closes it. Both DEA agents stare intently at me.

“Go ahead,” Tim says, narrowing his focus on me as he folds his hands over the conference table.

With everyone’s full attention, I begin slowly. “I’m here today because I was involved in an operation that moved thousands of pounds of marijuana from Los Angeles to Ohio using private planes.” I pause for a moment, stifled by the sound of my own voice. The words seem so surreal coming from my mouth. I still can’t believe that what I’m saying is true.

“I want you to know that I knew what I was doing. I knew it was marijuana in the suitcases, and I did it anyway. The stupid decisions I’ve made have disappointed not only myself, but my family and all my loved ones as well. What’s done is done, and I can’t take any of it back. I can’t go back in time and make better decisions. The only thing I can do is try to start making good ones now and help you with your investigation as much as I can. That’s what I’m here to do.” When I finish, I look around the table at Tim Pritchard and the DEA agents. Each one of their postures has changed. The heat that was building in the room has begun to diffuse. They appear to be relieved.

“Well,” Agent Heufelder says as he exchanges a glance with the prosecutor, “I’d say that’s a good way to start the meeting.” He picks up a pen and leans forward with his elbows on the table. “All right, Meili,” he says. “We’re ready to listen to you. Why don’t you begin by telling us why you moved to Los Angeles?”

2

FRESH OFF THE BUS

Five years earlier. I was nineteen when I left my small hometown of Bremerton, Washington, to become a movie star in Los Angeles.

Ever since I could remember, a career in film seemed like a perfectly reasonable pursuit. I’d never found anything, short of the Backstreet Boys, that excited me in the way that acting did, and almost nothing else that made me feel particularly special. I was a strange, chubby child during my early years of elementary school, with a misguided sense of fashion and a misinformed belief that shampooing one’s hair too often could be destructive. My wardrobe was a combination of colorful L.L.Bean vacation clothes and GAP denim hand-me-downs from my male cousins. I had my ears pierced at a young age, and I had an obsession with dangling earrings. I would beg my mother to let me wear hers to school. I most adored her Christmas earrings. In my opinion, they were the most beautiful of all her jewelry, with their intricate balls of glitter, vibrant jewel tones, and even one pair that had blinking red and green lights. I never viewed myself as being pretty, but I felt a little pretty when I wore her holiday earrings, with no regard for the ridicule that they might inspire from my classmates. My mother would look at me with hesitation and concern when she’d find me wearing them after January and well into the summer, but she never had the heart to tell me not to.

I’d grown accustomed to being bullied at school, mostly about my weight. I was only marginally overweight, but, combined with all my other oddities, it was enough to fill any afternoon recess with cruel jokes at my expense. I compensated for my apparent social repulsiveness by acting goofy and playful, and it won me friends, though it came at the cost of daily badgering. I think we were all just trying to fit in.

Throughout every awkward and often painful phase of my childhood, my involvement in local theater was my escape, my happy place. I planned to one day escape forever to L.A. and the artful world of cinema, where I was sure I’d find acceptance.

My great-aunt on my mother’s side, who died years before I was born, was a silent film star known as Wanda Hawley. That was her stage name; her real name was Selma Pittack. She was a contract actress with Paramount Studios and rose to fame as the ingénue in a string of Cecil B. DeMille films. Wanda became the envy of many women of the time when she starred as the love interest to screen legend Rudolph Valentino in a film called The Young Rajah. I read online that at the

peak of her career, she was receiving just as much fan mail as, if not more than, Gloria Swanson.

According to family lore, Wanda was disowned by some of the family after it was discovered that she had been dancing naked on a table with some other actress at a party. When I heard the story from my parents, I was awed by how confident and free-spirited she must have been to do such a thing. Unfortunately, my great-aunt’s career never thrived beyond the advent of sound in movies, and the small amount of money she had left from her days as a screen star was gone by the time she died. She was buried in the famous Hollywood Forever Cemetery on Santa Monica Boulevard, right across the street from her former home at Paramount Studios. Just outside of her concrete resting place, the Paramount Water Tower is in plain view, looming in the skyline.

In my bedroom growing up, I had two framed photos on my wall that had once belonged to Wanda. One was an old headshot that she’d signed on the back “with love” to her brother. The other was a photo of her being interviewed by a journalist for Harper’s Magazine. I kept both pictures in their original frames as keepsakes from Wanda’s better days. I looked up to her. She had gumption. She was one of the first big stars in the history of the industry, one of the first people who really made it. Though it didn’t last, she had her moment in the sun. I could only imagine how invigorating it must have been, to be a working actress in Hollywood. I longed to experience that, and I swore that someday I would.

By the time I entered junior high, I had slimmed down and grown into a full C cup. I joined a neighborhood gym and started going to Weight Watchers meetings with my mother. I lost almost fifteen pounds and was stunned to find myself getting positive attention from boys, for the first time in my life. Fresh from summer vacation, I came back to school tan and toned in a way that I’d never been. I was armed with makeup and a hair straightener, and my parents were kind to supply me with a new wardrobe of well-fitting clothes.

In high school I was active in the Rotary Interact Club and the Honor Society. I was voted Rotary Student of the month, student body president, homecoming princess, and “Most Likely to be Famous” by the time I graduated. I’d managed to save five thousand dollars working at a coffee stand on the lot of a gas station near my house and spent the money on a backpacking trip through Europe the summer after graduation. I came back ready to make good on a promise I’d made to myself years before.

APRIL 2005

Dressed for the road, I stood in our living room. The walls to our Northwest house were covered by long windows, and from almost anyplace upstairs one could see a landscape of grass, garden, and dense forest that surrounded our property. My father made a fire in the woodstove that kept us warm all morning as we prepared for the drive south to Los Angeles. He’d tried many times to teach me how to build a fire, but I never really learned; maybe now I’d never need to know. I wondered if I would ever miss Bremerton and its morning frost. It’s beautiful here, but often so cold—I was looking forward to the sunshine of Southern California. Spring had barely arrived, but I could see from the living room window that the apple tree in our backyard had already started to bloom. I wouldn’t be around for Mom’s apple pies this year. Over our acre of trimmed lawn, I took in the view of the Hood Canal and the Olympic Mountains one last time before turning to go outside.

With the help of my parents, I loaded the greater part of my worldly possessions into my used Volkswagen Jetta. My mother stood in her nursing scrubs and worn clogs on our gravel driveway. She works at a clinic in town. My dad is a real estate agent and makes his own schedule. He insisted on driving down to Los Angeles with me, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way. He secured the last of my boxes into the trunk. “Well, looks like we’re all set, sweetie,” he said. “I’ll grab the cooler. Mom packed us up some snacks. And I smoked the last of that salmon from Neah Bay. I thought we could have a little on the drive. I’ll tell you, it’s pretty good! Might make you want to rethink your move! I can always turn the car around.” He grinned at me. My parents always knew that I would move to Los Angeles someday, but it didn’t stop them from trying to lure me away from the plan with homemade goods and the best smoked salmon this side of the Olympic Mountains.

My mom put her arm around me. “I hope you can forgive me for working today,” she said. “I just thought that because you’re leaving before I am, that it would be okay.”

“Mom, no,” I said. “Why would you take the day off? It’s perfectly fine.” She nodded and leaned her head against mine, squeezing my arm as she pulled me in closer to her. She brushed a long strand of rust-brown hair from my face and looked at me with wet eyes. Her hands were soft and smelled like Oil of Olay. I kissed her on the cheek. My father arrived back with the cooler and looked at his watch.

“Okay. We have to hit the road if we want to beat traffic,” he said.

After a few minutes of increasingly tight hugs and “be safes,” my mother stayed anchored on our porch. I climbed into the passenger seat of my now fully packed car and rolled down the window as Dad started the engine. My eyes were locked on my mother’s. I had so many memories of seeing her standing at that same spot, on the porch at the doorway to our home. My older brother, Nick, and I used to come back from school and she would be there and open the door for us before we could reach it. Now, it had been over a year since Nick left to study physics at Stanford, and I, the youngest, was about to be the last to leave.

Mom waved as my Jetta pulled down our driveway, bound for Hollywood. I watched her get smaller in the rearview mirror. She blew kisses and wiped away tears that poured down over a tight smile. She continued to wave to us with her free hand. The image ripped at my heart. I knew it would.

My father and I drove as close to the ocean as we could. The Jetta had a sunroof, and we cruised down the West Coast with our hands stretched toward the sun, catching salt air and blowing it into the car. The sound track to the movie Chicago blared through the speakers, and the only noise that could be heard above it was the off-key caw of our voices as we sang along at full volume. We turned a twenty-two-hour drive into a three-day road trip, with my father enthusiastically stopping us at every conceivable tourist attraction along the way. We followed the Pacific Coast Highway through Malibu and, when we saw palm trees and giant movie billboards on the Sunset Strip, we’d finally arrived at my new home in Hollywood.

The movies I saw glowing on those billboards were filmed here. The actors who starred in them lived here. I knew I could be one of them soon. There were curbside taco trucks with neon signs that flashed bright long after the bars were closed. Drunks stumbled out of nightclubs like zombies, ready to commit carbocide (i.e., death to one’s diet by extreme intake of carbs) after other more salacious ambitions for the evening had been abandoned. This town had a pulse. Good, bad, or perverse, it was alive.

I SETTLED INTO THE SPARE bedroom of a small duplex near Sony Studios in Culver City, close to the ocean, though just out of reach of the salt air. My roommate was an elderly Mexican woman named Esther, the mother of a family friend in Washington. She spoke very little English, and my three years of Spanish in high school didn’t help much to bridge the gap; but Esther seemed nice, and the rent was cheap. I was finally in Hollywood, where everything started for Aunt Wanda, and now where I was beginning my own career.

I enrolled at an acting studio in the San Fernando Valley. I’d found out about the class from one of Dad’s coworkers back home, who claimed to have been an agent at William Morris once upon a time. The class was in a room on the upstairs level of an aging strip mall on Ventura Boulevard, next to a Mexican restaurant. The studio space held forty theater seats that had been recovered from old movie houses, facing a spot-lit stage area.

The instructor was a flamboyant, blond sixty-something woman named Bonnie Chase who talked about “the good old days of Hollywood” and a former love affair with Jack Nicholson. The walls inside her studio were plastered with actor headshots; some of the photos were new, in color, and some were old and staine

d in black and white. I recognized a few of the faces from movies and television. There was a picture of Bonnie with Anthony Hopkins taped to the door, amid a collage of personal photos of Bonnie with other celebrities whom she said had studied with her over the years.

MY FATHER AND I HAD flown down to visit Los Angeles a month before my move. That was when we first came to the studio and met Bonnie Chase, following up on his coworker’s referral. Dad wanted to meet the woman who was about to be my acting coach, and of course I was eager to get a look at the class.

Bonnie had told us to come in on the Thursday that we’d be in town during our visit. Thursdays at the studio were showcase nights, when Bonnie invited “industry professionals,” such as directors and agents, to come watch her actors put up scenes, similar to a variety theater performance. When we came to watch the showcase that night, Bonnie had introduced my dad to her students as a “producer.” He laughed it off, though we both thought it was odd.

The talent at the showcase was intimidating, a far cry from my high school drama department, and these actors had steel in their eyes. They were fighting in every scene to be the best, and some of them were pretty damned good. The competition in this town was fierce.

After the showcase, Bonnie invited us to a birthday party the next night for someone named Daniel, who was apparently a friend to many people at the studio. Daniel wasn’t an actor, but he was peripheral to the film industry as the former assistant to a well-known director. Dad and I accepted the offer, thrilled to be invited to my first party in L.A. The birthday celebration was to be held at a hotel bar in Hollywood; being nineteen, I was worried that I wouldn’t be allowed in, but an actor from Bonnie’s studio said that security was usually pretty loose and I’d have a good chance of getting by without showing an ID.

At our hotel room before the event, I unpacked a black-and-gold sequined dress from Forever 21. Dad had bought it for me the week before our trip, just in case we went out while we were here. He’d wanted me to have something new to wear. I wore bright yellow stilettos from Ross I’d been saving to wear for a special occasion. They were the tallest shoes I’d ever owned, but I thought they were sexy and worth a little discomfort. Bonnie had told me to look my best: there might be directors or people in casting at Daniel’s party, and it could be a good opportunity for networking.

Smoke

Smoke